Ashdown Forest, Home of the Great Bear, and a 19th Century Country House

A Brief Orientation

|

| East Sussex |

|

| The County of East Sussex Ashdown is 5km NW of Crowborough (a third of the way to East Grinstead). Standen is west of Forest Row, just inside the county boundary |

Ashdown Forest

AA Milne, Winnie-The-Pooh and Christopher Robin

.jpg) |

| AA Milne in 1922 Photo:Emil Otto Hoppé (Pub Dom) |

|

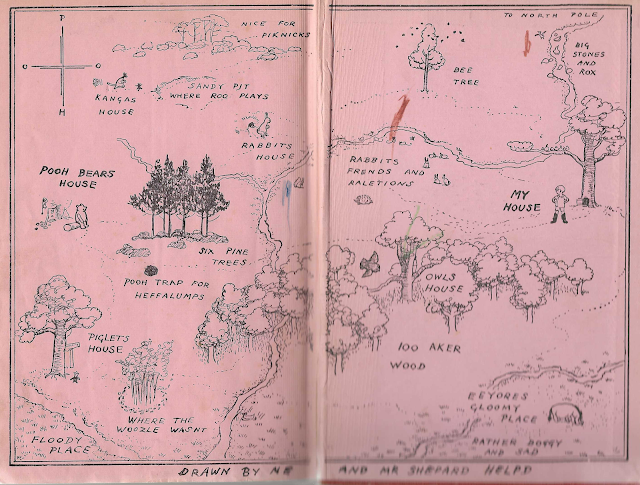

| The Hundred Aker Wood |

In reality he put away his soft toys and went to

boarding school. Sending nine-year-old children away to school is cruel and is

far less common now that it was in Milne’s day, but the Milne family, like most

of their class, had been doing this for generations. His father's books were

well known by his schoolmates, making Milne a target for relentless bullying. He

came to resent Christopher Robin and, by extension, his father. They were later

reconciled, and he found his place in life as Chris Milne, Dartmouth bookseller.

The Pooh books and the two books of poems rather swallowed

AA Milne's career. They were extraordinarily successful and today are his only works

still in print – which is, I suppose, four more than most writers of his

generation.

I knew nothing of this darker side when the Pooh books

were bought for me in 1955. They are first editions - though from the 46th and 35th

reprints of the two books, so hardly valuable (at least in a monetary sense.)

They are tatty, because they were much loved and they were frequently read to

me and then by me and then to and by my sister. They started my relationship with The Great Bear (as I like

to think of him) which has lasted 70 years.

Towards an Enchanted Place

Peter drove us to the

Ashdown Forest and stopped in the Pooh Car Park. From there an unlikely looking

group of volunteers for enchantment made their way down the path.

|

| Up for enchantment? L to R Me, my sister Erica, her husband Peter |

The grey February day with passing showers, was not promising but then somebody spotted Piglet’s House.

|

| Piglet's House |

Is this, though the real Piglet’s House? The only information we have comes from the illustrations (he called them decorations) of EH Shephard, who was there at the time – unlike the outrageous

fakers of the Disney Corporation. He includes a broken sign saying ‘Trespassers Will’, because Piglet’s grandfather had been called Trespassers William, but here the sign has been mended, changed shape and hung above the door. I have my doubts.

|

| Piglet's House |

Here is another photo of Piglet’s House with my sister

for scale. She makes it look ‘deceptively spacious’, to quote every estate agent who has ever lived.

|

| Erica visits piglet |

A little further on is Owl’s House…

|

| Owl's House |

… which you might like to compare with the original.

|

| Owl's Real House - rather more accessible |

I had my doubts, but when you see random pots of Hunny in the trees and know the Great Bear would never be so careless, these doubts begin to crystallise (just like Hunny).

|

| Hunny left in trees |

Then, with the rain spattering down, we reached the stream at the bottom of the hill, turned right, and there was the Pooh Sticks bridge.

|

| Pooh Sticks Bridge |

I was, of course, being disingenuous earlier, EH Shepard’s illustrations/decorations do not inform us about Piglet’s house, they define the dwellings of Piglet, Owl and the others. When

the reality we see in the trees differs from the art, then it is the reality

that is wrong – but they were constructed by people who cared enough to do it,

and not for financial gain. They should be applauded.

But the Pooh Sticks bridge introduces another form of reality. The bridge we see today is the same bridge that stood here 100 years ago – give or take the repairs and renovations required to keep a wooden bridge over a muddy stream in good condition for a century. Shepard did not need to imagine the bridge, but did have to imagine a bear, a piglet, a baby kangaroo and a rabbit who have just dropped sticks into the stream.

|

| Pooh and Rabbit play Pooh Sticks |

Getting a couple of pensioners to imitate them is easy. Shepard, I notice, gave more interesting expressions to Pooh and Rabbit with a few strokes of a pen, than we managed

with our actual faces.

|

| Less adept players of the game |

During Pooh and Rabbit’s game, Looking very calm very dignified, with his legs in the air, came Eeyore from beneath the bridge.

|

| Eeyore emerges from under the Pooh Sticks bridge |

“It's Eeyore!” cried Roo,

terribly excited.

“Is that so?” said Eeyore, getting caught up by a little eddy and turning slowly round three times. “I wondered.”

I include that snippet of Eeyore being delightfully Eeyore-ish, because when it was read to me in nineteen fiftysomething I learned a new word. Eddy was, I thought, a grand and exciting

word and I treasured it. It also allowed me to show my favourite illustration of Eeyore.

While we were at the bridge two young people, a man and a woman in their early 20s, came down the path towards us and politely inquired the way to Pooh’s house. We pointed them

in the right direction. It is ridiculous to imagine you know anything about

people you have met for no more than a minute, but… they gave the impression of

being foreign students cast up on this dank and misty island (not everyday, but

certainly this day) in a quest for knowledge. They spoke good English, but it was not their first language. Indeed,

they probably did not share a first language, but they had come together to this

place to search out the origins of Winnie-The-Pooh. The Great Bear embraces the

world.

Pooh’s house is over the bridge and further down the path. We passed the students (or not-students) making the return journey.

|

| Pooh's House |

I will forgive the muddiness of the scene; this is February while the Hundred Aker wood enjoyed the sunshine of perpetual summer. I could be picky about some positionings and spellings,

but EH Shepard has drawn Pooh sitting outside on a comfy log, implying the door

opens inwards, which is somewhat impractical if you live in a tree trunk.

|

| Pooh's House |

The Wonder that is Pooh

As the final story in Winnie-The-Pooh (the first of the two books) comes to its end

Pooh and Piglet walked home thoughtfully together in the golden evening, and for a long time they were silent.

“When you wake up in the morning, Pooh,” said Piglet at last, “What's the first thing you say to yourself?”

“What's for breakfast?” said Pooh. “What do you say, Piglet?”

“I say, I wonder what's going to happen exciting today?” said Piglet.

Pooh is my sort of bear. Excitement and adventures are all well and good, but first things first.

Milne’s writing is crisp and simple, the words jogging along, one after another. There is plenty of humour directed at children, Pooh attacked by

bees while dangling from a balloon, or trapped in rabbits burrow by his ever-increasing

girth, but even the slapstick is elegantly restrained. The characters are

fully formed and three-dimensional. When Pooh and Piglet plan their heffalump

trap they argue about the best bait for catching heffalumps. Pooh, naturally,

says honey, Piglet acorns. As they argue Piglet realises that if he wins, he

will have to provide the acorns, and if Pooh wins, he must provide the honey. Piglet

quickly switches sides. As he does so Pooh realises the same thing, but too

late, he has been caught out. He takes it on the chin, as a gentleman should.

The characters have frailties, Piglet’s occasional selfishness, Owl’s permanent

self-importance, Eeyore’s moroseness, but malice is unknown in the Hundred Aker

Wood.

|

| EH Shepard in 1932 Howard Coster (Fair Use) |

Milne’s voice contains a smile that is sardonic, yet very gentle; a knowing nod to the adults over the heads of the children. The writing is very British, understated and still feels surprisingly modern, Nothing in the two books seems dated – except the way

Christopher Robin dresses, and that looked odd in 1956. In the final story,

when Christopher Robin leaves the wood, the animals gather to say goodbye

and send him off with ‘a rissolution.’ They all want to express their feelings,

as does Christopher Robin but they cannot trust their emotions. One after

another, they clear their throats to speak but say nothing, and one by one all,

except Pooh, drift away. And I shall drift away too (without deigning to deal

with the blasphemies of the Disney Corporation) but I must make a final mention

of illustrator Ernest Howard Shepard who unfailingly places the cherry in just

the right spot on Milne's artfully baked cake.

Standen House

Leaving Ashdown Forest we headed for Standen House, a National Trust property some 20 minutes to the west, and like the Forest, situated in the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Lunchtime had

arrived so we visited the café in search of a little smackerel, as Pooh would have

said.

|

| Philip Webb 1873 Charles Fairfax Murray (Pub Dom) |

The house was designed by Philip Webb, a founder of the Arts and Crafts movement, and built between 1891 and 1893. He integrated the medieval farm building into the vernacular design using local sandstone, local bricks,

tile-hanging, pebble-dash and timber all chosen to harmonize with the landscape.

My photo shows only one wing - there is more piled on top to the left. Perhaps

it is just me, but I am unconvinced the building harmonises with itself, never

mind the landscape.

|

| Standen |

Margaret Beale took charge of the interior. She commissioned wallpapers, carpets, textiles and furniture mostly from William Morris & Co, all reflecting the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement.

|

| Original William Morris wallpaper, Standen |

Philip Webb built in modern comforts, like central heating and off-grid electricity provided by a Donkey Engine. The house certainly looks more comfortable than most older National Trust properties. Visitors see

the house dressed for a weekend stay in 1925 and the parlour looks comfortable

enough, in an early 20th century way,

|

| The parlour, Standen |

The conservatory looks a little cluttered…

|

| The conservatory, Standen |

…but I would like a billiards room like this.

|

| Billiards Room, Standen |

The Larkspur bedroom was re-papered in 1937 with William Morris Larkspur wallpaper. It also featured a built-in wardrobe, uncommon for the time, with an external mirror, designed for the Beales’ eldest

daughter Amy.

|

| The Larkspur Room |

James Beale used to sometimes see clients at Standen. He had an office with a door into the house for himself and another for clients with access only to the outside. He is still there, but only as a sketch by one

of his daughters.

|

| James Beale's Office, Standen (and a National Trust Volunteer) |

The hillside garden behind the house is, I read, spectacular. William Morris said a ‘house should be clothed by its garden,’ but gardens are not at their best in February, and certainly not on a miserable day

like today. We chose not to wander round it in the rain.

|

| Are we having fun yet? |

James Beale died in 1912. Margaret remained here until 1936, followed by her daughter Margaret (“Maggie”) and youngest daughter Helen. The house remained largely unaltered over decades and Helen Beale, who had been involved in nursing during WWI and later the WRNS, bequeathed Standen to the National Trust in 1972

Part 1:Bodiam and Rye (2020)

Part 2:Bateman's, Firle Beacon and the Long Man of Wilmington (2021)

Part 3: Battle and Hastings (2021)

Part 4: Rottingdean and The Devil's Dyke (2024)

Part 5: Lewes and Charleston (2024) (coming soon)

Part 6: Brighton and the Royal Pavilion (2025)

Part 7: Winnie-The-Pooh and Standen (2025)