This is the third and final of my 65th birthday posts. It follows directly on from

and

In the morning Hossein Afshar conducted a tour of Abadan,

and there is no one who knows more about the city.

We crossed Breim, pausing briefly at his old house, and

reached the northern shore of the island, passing the AIOC artisans’ dwellings.

Built back from the coast they were denied the cooling breezes from the Gulf,

but received the refinery fumes in compensation. Like the houses in Breim some

were empty and decaying. A little further on the bridge to Khorramshahr was

closed. The surrounding area had grown

up more recently and was little more than a shanty town with a tatty fly-blown

market. We followed the coast westwards to a bridge under construction and then

headed down the other side of Breim.

|

| The part constructed bridge over the Karun from Abadan to Khorrmashahr |

Here we would have seen the biggest and most imposing houses,

but this area was within easy range of Iraqi artillery. During the Imposed War

(or the Iran-Iraq War as we usually call it) the Iraqis invaded and occupied

Khorramshahr, but never came onto Abadan Island, contenting themselves with

lobbing shells across the Shatt-al-Arab. Most of the buildings still lay in

ruins, the house of AIOC’s top man in Abadan, later a residence of the Shah,

was a burnt-out shell.

|

| Once the Abadan residence of the Shah |

The road ended in a bank two metres high. Beyond was the

river and beyond that Iraq, a land the authorities did not want us to see or

even think about. Police stations and army posts were much in evidence and I

had to take great care how I used my camera.

|

| Damage from the Imposed War (The Iran-Iraq War), Abadan |

Nearby, the Gymkhana Club was once the watering hole of the

Abadan elite. During the 1951 riots much was made of the sign outside saying

‘No Dogs, No Iranians.’ ‘It never existed,’ Mr Afshar said. ‘It was invented for

propaganda purposes.’ Despite its once well-stocked bar, the club looks like a

village hall which should be somewhere else, but is held hostage in Abadan by a

high fence and formidable iron gates.

|

| The Gymkhana Club (with the refinery in the background) Abadan |

The Church of England chapel had been destroyed long ago,

though whether by neglect or malice was uncertain, and the gravestones in the

expatriate graveyard were largely illegible. N hurriedly stopped me taking photographs as the church backed onto a police station and I was being watched

by suspicious eyes.

|

| The Site of the C of E chapel and the expatriate cemetery, Abadan |

We left Breim and passed the refinery. Here the road came to

the water's edge so the authorities could not prevent views of Iraq. Across the

river was a green land fringed with palm trees, it hardly looked a threat to

world security.

Planning their leave in 1951, my parents felt that their

infant son should be gently acclimatised to the rigours of the north European

climate. My mother and I left early, taking the slow route aboard the BP tanker

‘British Patriot’; my father flew out later. The jetty from which I embarked on

the tanker is still there, if unused and unloved.

|

| Probably the jetty from which I left Abadan in April 1951 |

The refinery bristled with ‘No Photographing’ signs and

watchful guards, so I held my camera by my knees, raising it for an instant as

we passed the jetty. Then we turned round and I did it again in case the first

one missed. ‘Once more,’ I thought ‘and we’ll be arrested as spies.’ I did not

dare photograph the refinery itself, once the biggest in the world but now

running at only two thirds capacity.

As I had expected, the AIOC hospital was indeed opposite the

AK Hotel although I had failed to notice it yesterday. At the entrance, despite

Hossein Afshar’s eloquent pleading, the gatekeeper would not let us into the

grounds and told me not to take photographs. I ignored him.

|

The Imam Khomeini Hospital, Abadan

Built on the site of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company nursing home |

Once a company nursing home, it is has grown into a large

modern hospital and is now named after Emam Khomenei. The Shah was indeed a

despot and needing overthrowing, but Ayatollah Khomenei, who led the

revolution, was an intolerant bigot. I look forward to the day, and it will surely

come, when his name is no longer attached to my hospital.

Round the back of Abadan town Mr Afshar continued his

commentary on the island’s development. He had been educated by the British and

worked with them for many years and remained a (not-uncritical) anglophile.

Probably unaware of the ‘what have the Romans ever done for

us’ sketch he described how the British had organised a piped water supply in

Abadan years before Tehran had such a luxury, and built a reservoir of

untreated water feeding a separate set of mains for irrigating the city’s parks

and green spaces. The British built hospital had originally been British

staffed but, he said, trained Iranian nurses who went on to work all over the

country. The houses of Breim and Bawarda were British built (by Costains using

bricks imported from Bahrain) so they did not fall down during the war - unless

they took a direct hit - and Abadan had its own television station, the second

in Iran (after Tehran, this time) long before there was a national network.

The British also provided Abadan with Iran’s first football

pitch. Football has since become big, to say the least, and the rejoicing when

Iran beat the USA in the 1998 World Cup Finals united the whole country. That

original pitch now has a stadium round it, four neat little concrete

grandstands that I estimated would seat some fifteen thousand spectators (update: the ground’s official capacity is now 25,000).

Inside is the brightest, greenest grass in all of southern Iran. Sadly Sanat

Naft, the Abadan team, were relegated from the top division of the national league

last year and must spend next season in the second tier

(update: they have been up and down several times since and are currently back

in the second tier).

|

| Sanat Naft Football stadium, Abadan |

We continued to the distinctive buildings of the British

built Abadan Technical Institute and then to the more recent Abadan Museum,

which was closed.

|

| Abadan Technical Institute |

Disappointed, we left the museum and almost immediately

arrived at the Taj cinema ...

|

| The Taj Cinema, Abadan |

...and the entrance to Bawarda.

In 1950 access was restricted to residents and, of course,

their servants. We drove in unchallenged and after only fifty metres I saw the

house. ‘There it is,’ I said confidently pointing to a building on our left. Mr

Afshar instructed N to take the next right. As we passed I looked for a number; I saw

a board with ‘SQ something’ on it, but the paint had peeled beyond legibility.

We drove slowly round the block whilst Mr Afshar examined the numbers, but we saw

no houses of the right design. After a complete circuit we were back to the

house I had first identified and this time I saw, written on the plasterwork of

the bay, the number 1495.

|

| SQ 1495, Abadan in 1950 |

“That is it.” I said, this time with complete confidence.

“So it is,” said Mr Afshar. “You know I lived next door for

three years, but that is 1553 so I always assumed this house was 1552 or 1554.”

There was little he did not know about Abadan, but we had taught him something.

|

| SQ 1495, Abadan in 2000 - with N's car in the drive |

The residents of 1495 were away, but there were servants in

the house; they were expecting us and invited us in.

|

| Inside SQ 1495, Abadan |

The bay contained a large living room, unfurnished except

for a Persian carpet. I immediately recognised the fireplace and mantelpiece

from old photographs but the picture hung above was purely Iranian. Behind the

bay was the bathroom. “That must be the original bath.” Mr Afshar sounded quite

excited,.“It’s got no mixer taps. It must be British.”

|

Servants quarters and the yard where Ali and 'Nanny' shared a hookah. (I suspect the air-con unit was not there in 1950)

SQ 1495, Abadan |

Behind the bathroom was a kitchen or, more properly, a

pantry because the real kitchen was in the servants’ quarters which were just

across the courtyard. My mother had often spoken of ‘Ali and Nanny’ sitting in

this courtyard in the evening, leaning against the wall sharing a hookah. My

imagination had seen a larger courtyard – here, a tall man would hardly be able

to stretch out his legs - but I mentally propped them over by the door, their hookah

glowing brightly as dusk fell. The arrival of a child, particularly a boy, had

discomforted this apparently contented childless couple. Much to his wife’s

distress my birth prompted Ali to spend time in the bazaar trying to acquire a

younger wife who could bear him boy children. Polygamy was not, and still is

not, illegal in Iran though the practice has all but died out. Ali never

carried through on his threat.

|

| Ali in my parent's kitchen, Mian Kuh, He later moved to Abadan with them |

There was a dining room opposite the bay and two bedrooms

behind, but there was no furniture in the house other than three fridges, two

of them in the back bedroom waiting to be unpacked.

There were several children, a youngish man and an older

woman who were milling round smiling. The older woman produced glasses of iced

cherry juice and we stood around, sipping and smiling lamely at each other. The

cooling system was not switched on and the house was over-warm and smelled of

damp. It was tatty and run down, inside and out. Mr Afshar apologised for the

state of the building, he could not understand the lack of furniture and seemed

a little embarrassed.

Lunch was offered, which is the Persian way, and declined on

our behalf by Mr Afshar, which is also the Persian way - you must offer three

times if you really mean it (and decline three times, if necessary). Hands

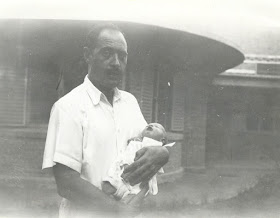

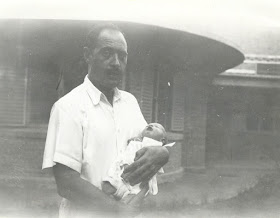

were shaken and we went outside for more photographs. I have a photograph of my father and myself (in pram) standing by a eucalyptus tree on the front lawn; on the back my mother, tongue firmly in cheek, had captioned it ‘My baby, my Eucalyptus’.

|

| My Baby, my eucalyptus |

I tied to recreate it, standing, as close as I could the very sod on which my father stood. Not having the original to hand I stood a little too close to the tree - and it surely must be the same tree, there too many points of similarity for it not to be (though I have no idea how long a eucalyptus will live)..

|

| His baby, his eucalyptus 50 years on. |

Bawarda was designed by James Mollison Wilson as a garden

suburb, a direct descendant of Hampstead by way of New Delhi where he had been

an assistant to Lutyens. My first home was a house with no architectural

parallel anywhere I know, in an Anglo-Indian style village tacked onto the end

of an Arab town itself tacked on to a Persian country. No wonder I was confused

about where I came from.

|

| My father and me, September 1950, SQ 1495, Abadan |

After what seemed only a few minutes it was time to move on.

I wanted to linger but I could think of nothing to justify extending our stay;

I could not just stand and stare at the house. As we drove away I turned in my

seat, watched SQ 1495 slip into the distance and helplessly grasped at the sands of time as they slipped through my fingers.

|

The Williams family, SQ 1495, Abadan, September 1950

Cute, wasn't I? How times change. |

I was sad to see so much decay and dereliction in both

Bawarda and Breim. Bawarda was built to house both Iranian and European staff,

but this innovative experiment in racial mixing failed, partly because Iranians

did not want to live in Bawarda and partly because the Europeans did not want

them there.

|

SQ 1495, Bawarda, Abadan, 2000

A last look |

James Mollison Wilson had assumed that Iranians living in

Bawarda would ‘desire British conventions of domestic life,’ and the houses were

designed ‘along the lines of a European house with such modifications as

climatic conditions impose.’ Northern Europeans live inside their houses;

people in the much warmer Middle East tend to live in enclosed courtyards

around their houses. Where Wilson went wrong was to build houses to live

inside, and as the damp in SQ 1495 proved, he badly underestimated ‘the

modifications that climatic differences impose.’ Building goes on apace across

Abadan while houses in Breim and Bawarda remain empty, and no attempt has been

made to repair the war-damaged dwellings. European style houses clearly fail to

meet local needs.

We returned to our hotel via the centre of Abadan town which

in contrast to Breim and Bawarda looked prosperous in an Arabic sort of way. A

mosque and the Armenian Church were companionably semi-detached – a model that

could usefully be followed elsewhere - and there were large well-maintained

banks and shops selling heavy gold jewellery as well as the more usual stalls.

|

| The centre of Abadan town |

In the evening Mr Afshar took us for a brief tour of

Khorramshahr . Saddam Hussein invaded Iran on the 22nd of September 1980 and

Khorramshahr was in Iraqi hands by the end of the year. They swept on round the

north of Abadan Island, but for reasons which are unclear they made no assault

on Abadan and no attempt to cut the last bridge. Abadan remained in Iranian

hands and connected to the mainland throughout the occupation. The Iraqis

fought street by street to take Khorramshahr and in 1982 the Iranians regained

it the same way. There was not a building that was not damaged or destroyed. I

had been impressed by the smart new buildings as we drove through yesterday. Now I realised that had been the new section of town, the rest looked dishevelled with

splatterings of bullet holes over the face of any building that was not new.

|

| Fruit stall, Abadan town |

Hossein Afshar might have once been the mayor of

Khorramshahr but after so much enforced rebuilding he had difficulty finding

his way around. After some circling we reach the corniche beside the Karun that

was built when he was mayor.

On the far side was Abadan island and on its shore old

ships had been brought to die. Rusting hulks by the dozen, launches, fishing

boats, coasters were tied up by the jetties or hauled onto the land where they

sat and rotted. If we looked right to where the Karun met the Shatt-al-Arab there

was the coast of Iraq, its date palms green against the sky.

My father learned only just in time that if I was not

registered with the British Consulate within three weeks of my birth I would automatically

become an Iranian citizen and they would have difficulty taking me home. He

hurried up from Abadan with Abed, his driver, and presented himself at the now long-vanished

building. They gave him the birth certificate I still have, half a yard long

and covered with enough official stamps to convince any observer that I was a

subject of the British King George VI, not of Muhammad Reza Shah.

|

| Abed, who was my father's driver for several years |

I photographed Mr Afshar on the corniche pointing at the

empty lot where the consulate had been. There this story ends, in the very same

place that it officially started in September 1950.

|

| Hossein Afshar and the former site of the British Consulate, Khorramshahr |

We took Mr Afshar back to the airport.

I had set out to find SQ 1495, or at least the site where it

once stood. Thanks to BP-Amoco and the generosity of Hossein Afshar I had

accomplished that and much more besides.

I had also wanted to find out something about my father who

died during the initial planning. We had never found it easy to talk and in

some ways I hardly knew him. I could not put into words exactly what I had

learned, but it felt significant.

As we parked I tried to find the right words to bid farewell

to Hossein Afshar, but as I searched my voice thickened and my final “thank

you” sounded lame.

We shook hands. He turned and walked off towards the

terminal.

Hello Mr. Dandly,

ReplyDeletebeing myself ""Abadani"", as we call ourselves born in Abadan, more or less the same age, I am of 1949 so only one year older, but I was lucky enough to live there (Bovarda Shomali) the North bowarda, until my dad's retirement which sent us to Tehran...but I loved reading your blog, because it brought back lots of good memories like seeing Taj cinema and the Technical college, but saddened a lot to see the damaged & destroyed houses of my beloved Abadan which I haven't seen it since 1962-63...thanks again for your nice blog & wishing you lots nice adventures & blogs .....

Hi Sir

ReplyDeletei Enjoyed of your articles about Abadan, my name is Roozbeh, 27 years old and i living in Abadan,now This city is better than 2000 years, Although it has not the grandeur of the 1950s, we Currently living with nostalgia. With your permission, i published again Your articles about Abadan at my website, With the details Including your name & your blog adress ... https://abadan1912.wordpress.com/

Thank you for your generosity.

I've read your blog with much interest and am fascinated by your photos. My parents both worked in Abadan - Dad worked in the shipping side organising the tankers and Mum was a nurse. I have letters which they exchanged. Dad lived at SQ57/2 which I understand was a flat and Mum in Sister's Quarters at Bawarda Hospital. I just wondered if you might be able to shed further light on where these would have been and any possible photos.

ReplyDeleteWith thanks and best wishes

Dear Rosemary

Deleteyou wrote that you have letters your parents exchanged.I am a history researcher may you send these letters.

your sincerely Hassan

I would like to know more about you and your family when you were living at Mian Kuh. My father was a worker In AIOC and i lived in Umidieh near Mian kuh.

ReplyDeleteI'm a PhD in history and writing a book about the history of Aghajari.

yours sincerely Hassan.

darvish38@gmail.com